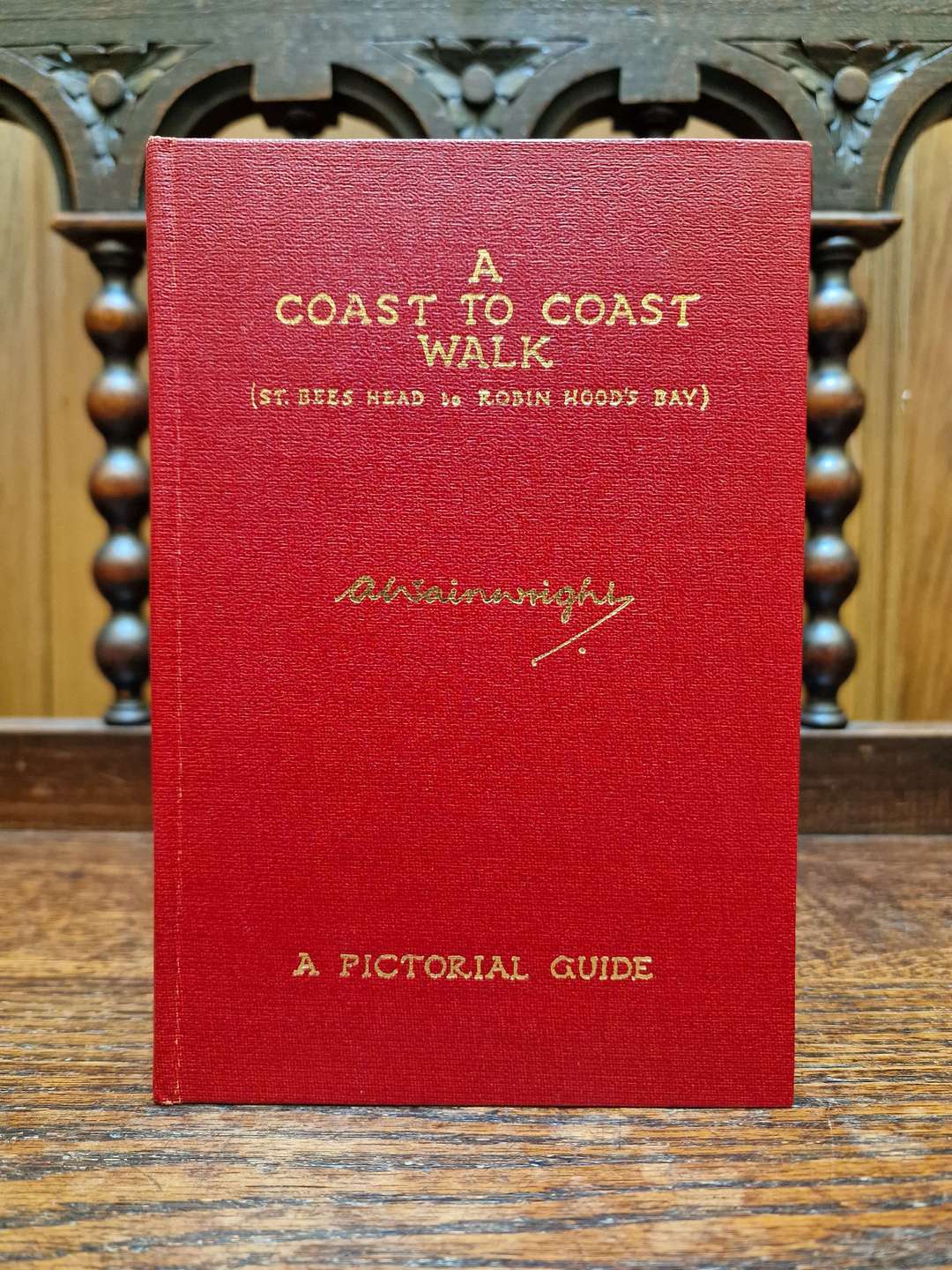

A Coast to Coast Walk

A Coast to Coast Walk was published in March 1973 and was dedicated to:

“THE SECOND PERSON (unidentifiable as yet) TO WALK FROM ST. BEES HEAD TO ROBIN HOOD’S BAY”

<<>>

Now over 50 years old, Wainwright’s Coast to Coast Walk stands as the pinnacle of hiking trails in the UK. This iconic 192-mile route traverses three National Parks: the Lake District, the Yorkshire Dales, and the North York Moors. Beginning at St Bee’s and culminating at Robin Hood’s Bay, the route is definitive. You start no further west and finish no further east.

Dissatisfaction with aspects of the Pennine Way spurred Wainwright to create his cross-country trail, which he believed showcased far superior scenery. He felt a ‘true’ Pennine Way should have started further south in Dovedale and ended at Hadrian’s Wall. Consequently, he considered the Coast to Coast Walk superior to Tom Stephenson’s trail.

Wainwright and Betty exchanged vows on 10 March 1970 and celebrated their honeymoon at the Viking Hotel in York, allowing Wainwright to begin fieldwork in the North York Moors. The project gained momentum throughout 1971 and reached completion by the summer of 1972. Wainwright’s creation was well received and was coming for the Pennine Way’s crown.

Unlike other long-distance paths in the UK, Wainwright’s route was unofficial by design. His intent is clear in the introduction and closing comments of the 1973 guidebook, where he encourages readers to embrace their creativity. Wainwright invites walkers to explore new, uncharted routes, venture off the beaten track, and seek solitude away from the crowds.

While much of Wainwright’s trail traverses private land and has seen revisions over the past five decades, its essence remains unchanged. When reading the guide, you can feel Wainwright’s love for his beloved northern landscapes on every page.

<<>>

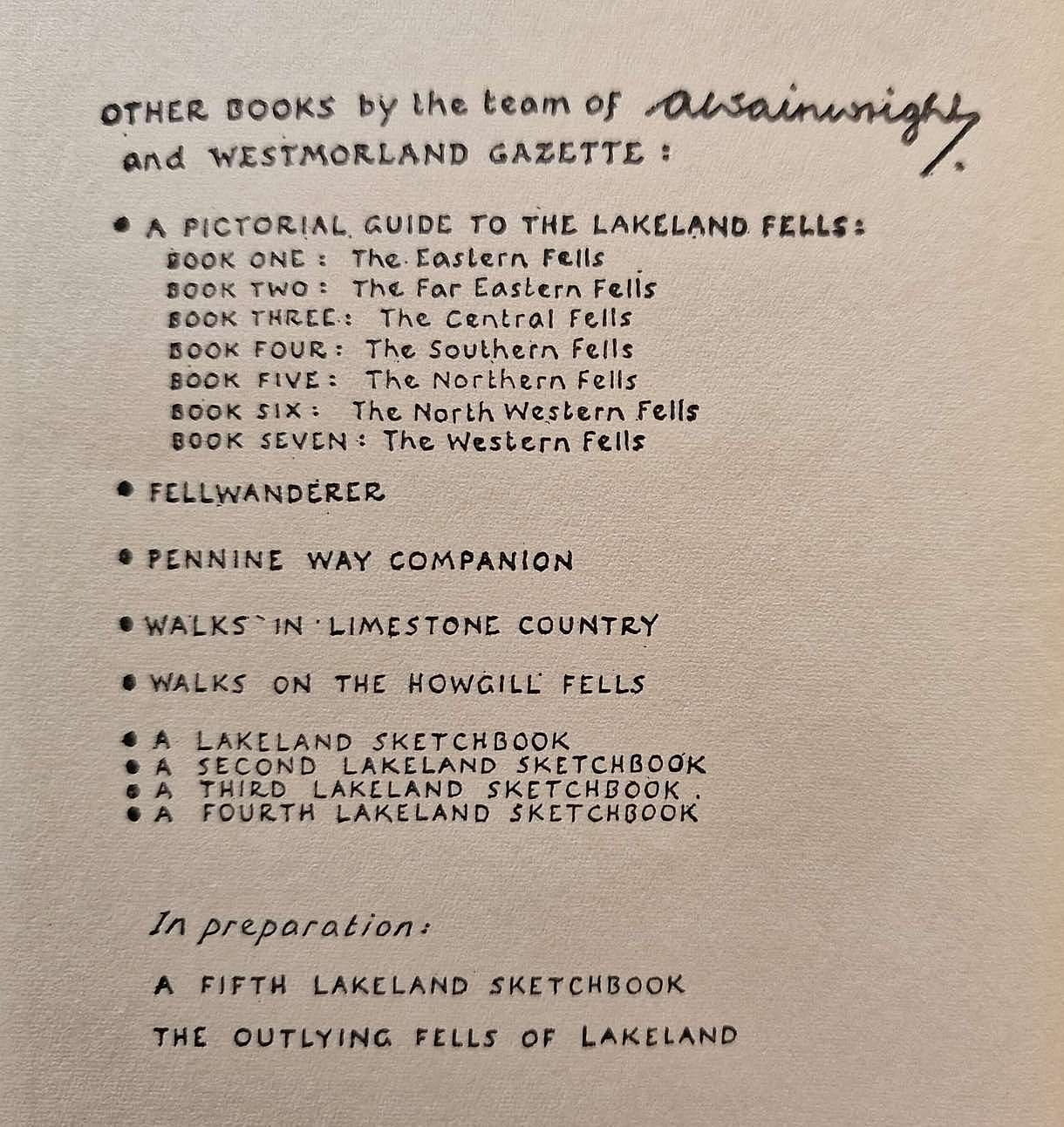

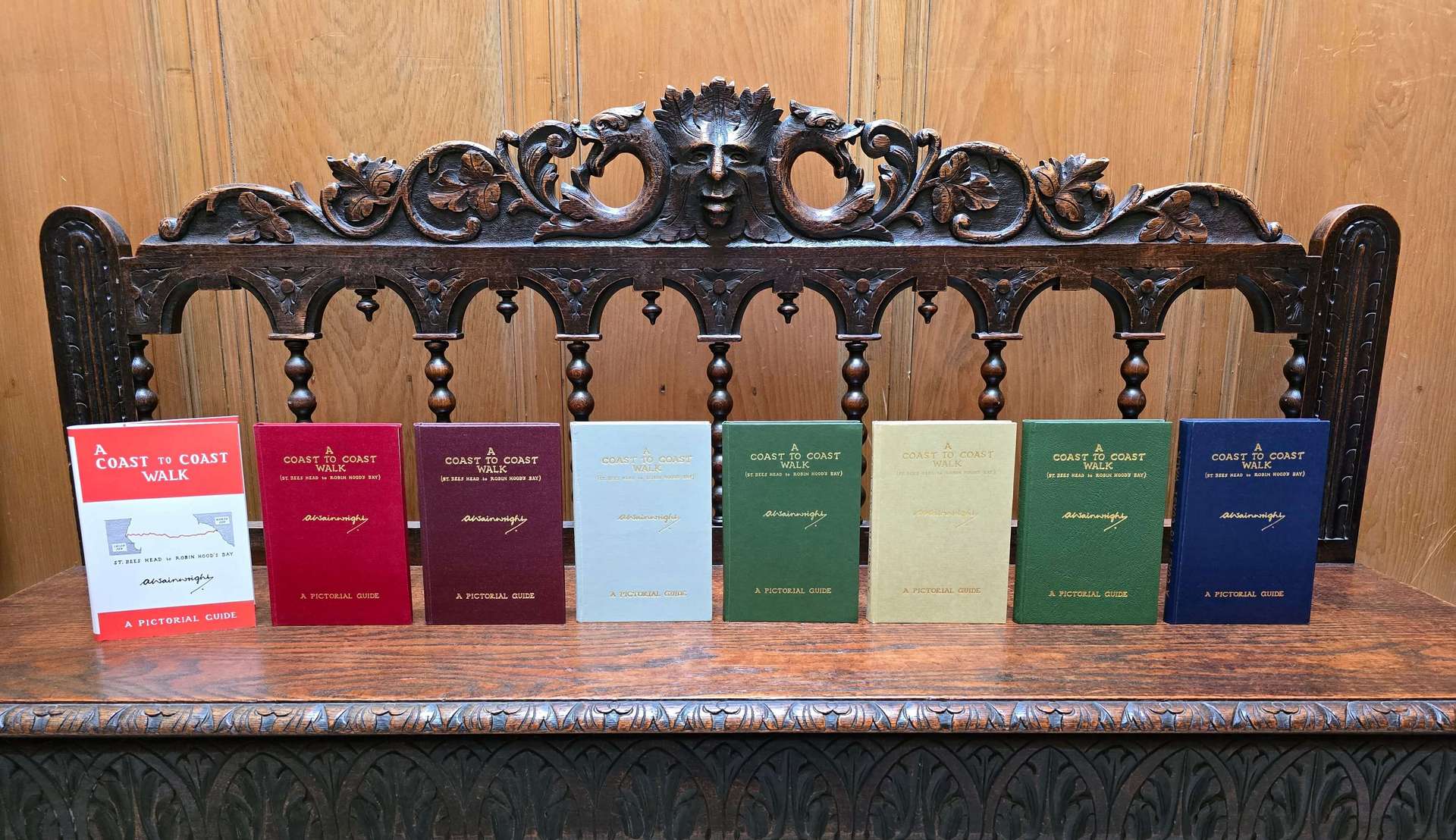

A First Edition is identified by:

- Red case with gold blocking

- £1.05 price on the dust jacket

- No impression number

The round-cornered guides had now been phased out, increasing production and saving money for the Westmorland Gazette. The vibrant red case colour, used for the first few impressions, is one of the loveliest colours in the series. Walks in Limestone Country used the same case colour.

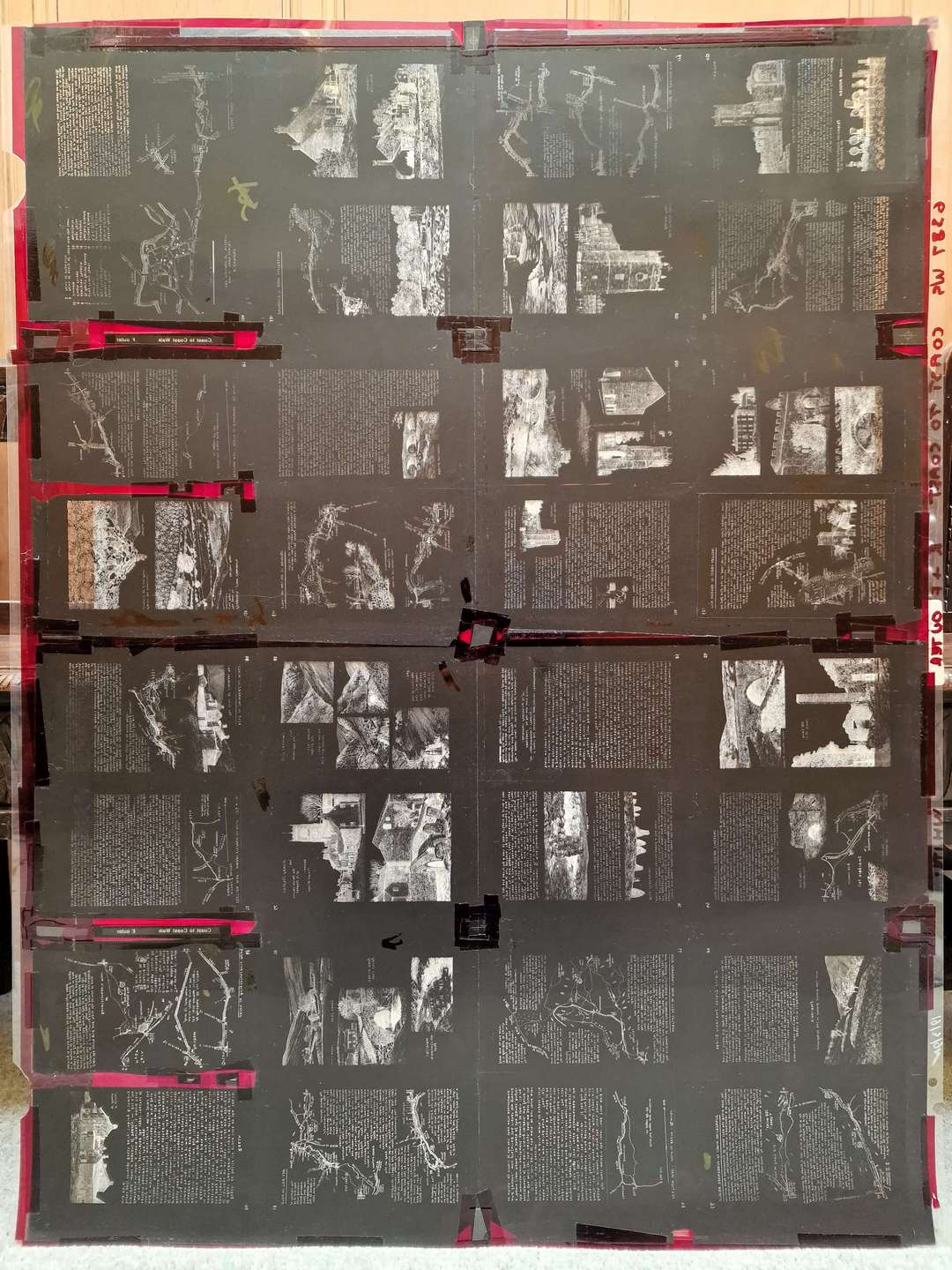

During the same decade, the Gazette transitioned from Letterpress printing to investing in offset litho technology. However, after almost 30 years, the original A Coast to Coast Walk printing negatives went missing. Fortunately, they resurfaced two decades later.

Many dust jacket negatives were repurposed and utilised for an extended period, often with either removed or concealed prices. The surviving negatives from the Gazette years are showcased here.

The Pennine Way Companion, Walks in Limestone Country and Walks on the Howgill Fells are the only other guides sharing the same £1.05 price. In contrast, the A Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells series initially retailed at 90p and increased to £1.40 in 1974.

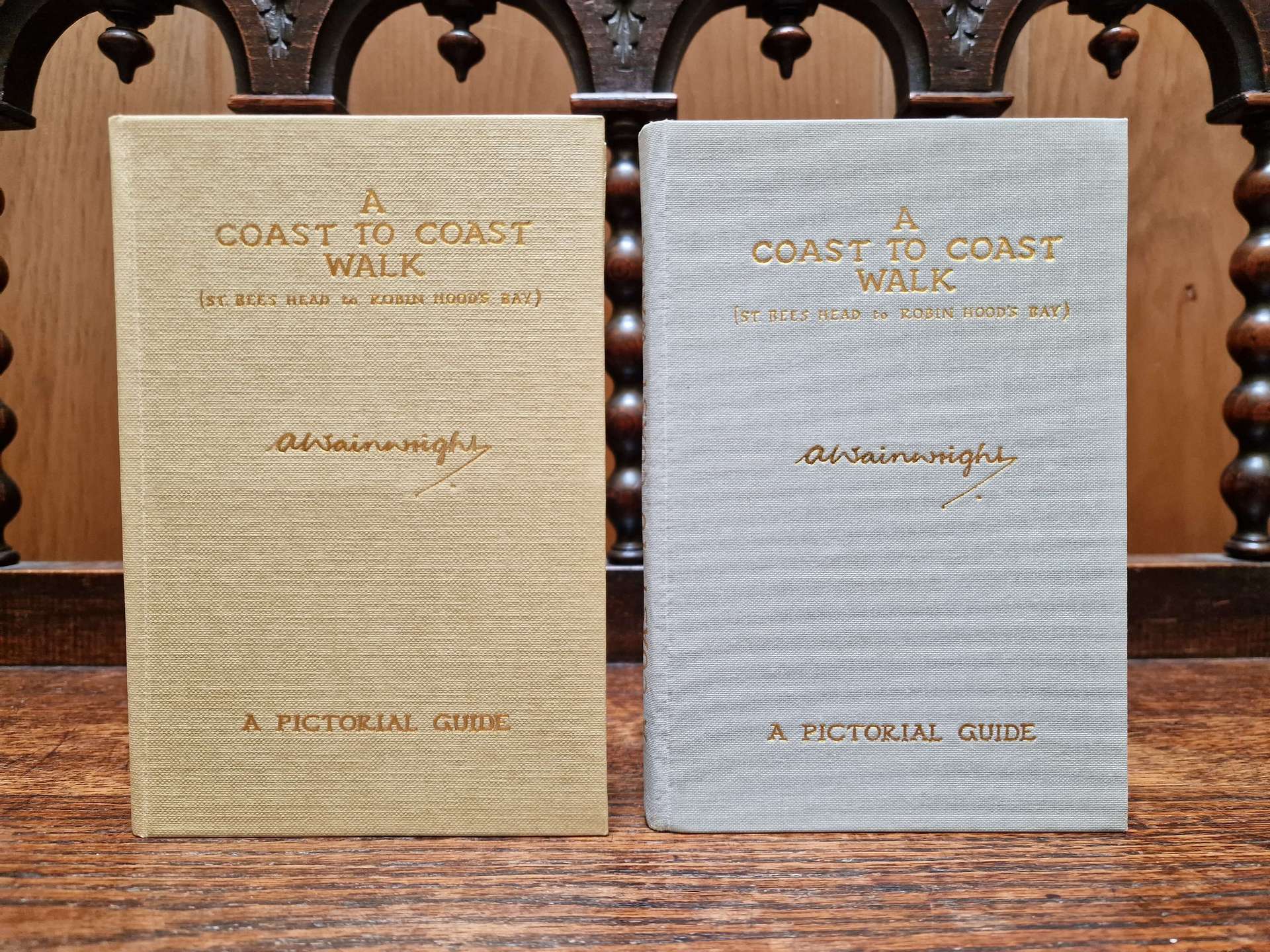

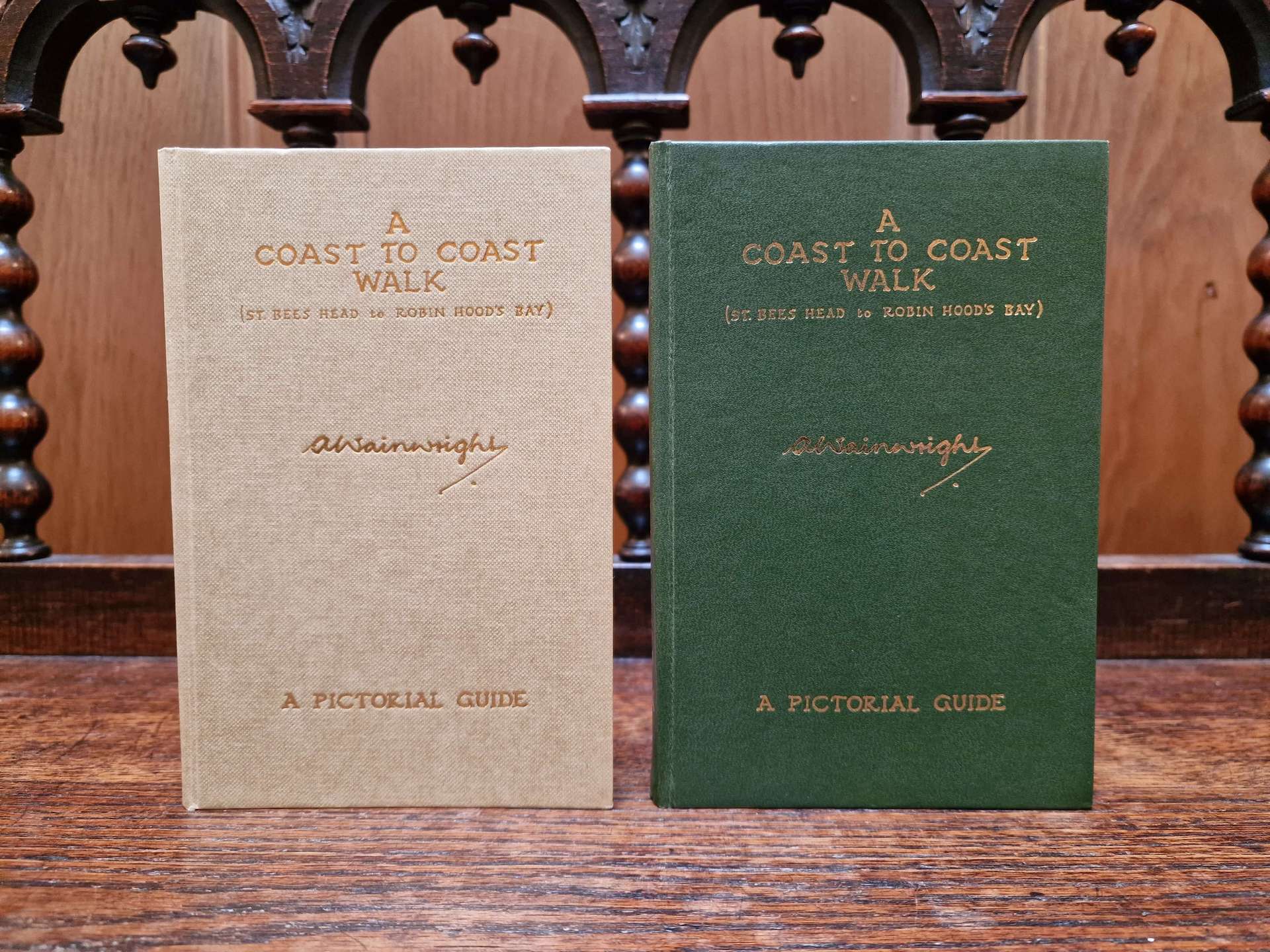

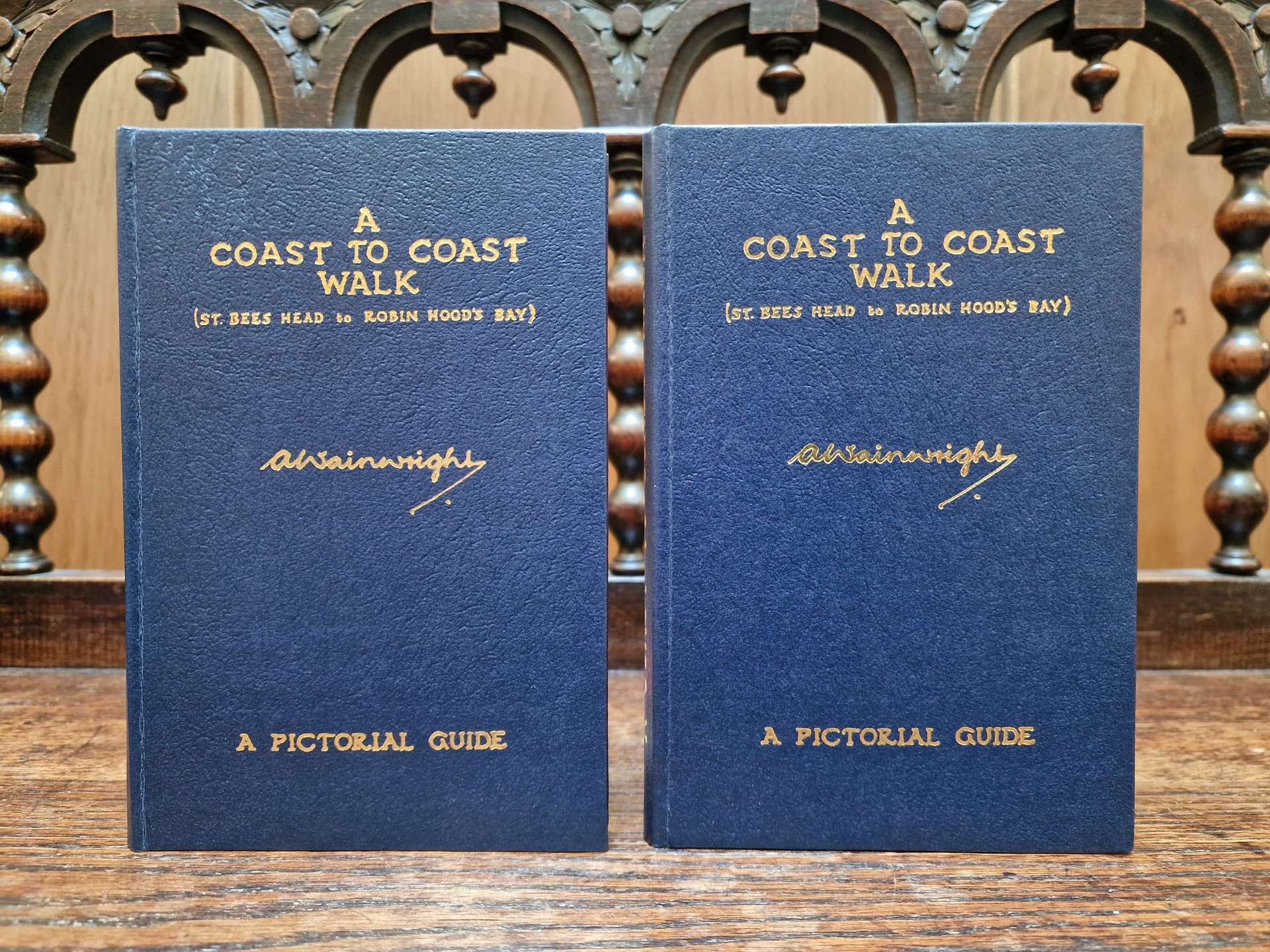

The initial five impressions of A Coast to Coast Walk sport the distinctive red clothbound case. However, a notable change occurred with the fifth impression, which was 50g lighter than its predecessors due to the adoption of lower GSM paper—a clear indicator of the onset of cost-cutting measures.

The A Coast to Coast Walk encountered case material shortages within a year of its 1973 publication. The scarcity of materials was so pronounced that they ran out during the binding stage. This led to several impressions utilising different case colours—notably, the fifth, seventh and ninth impressions, which feature various case colours due to these material constraints.

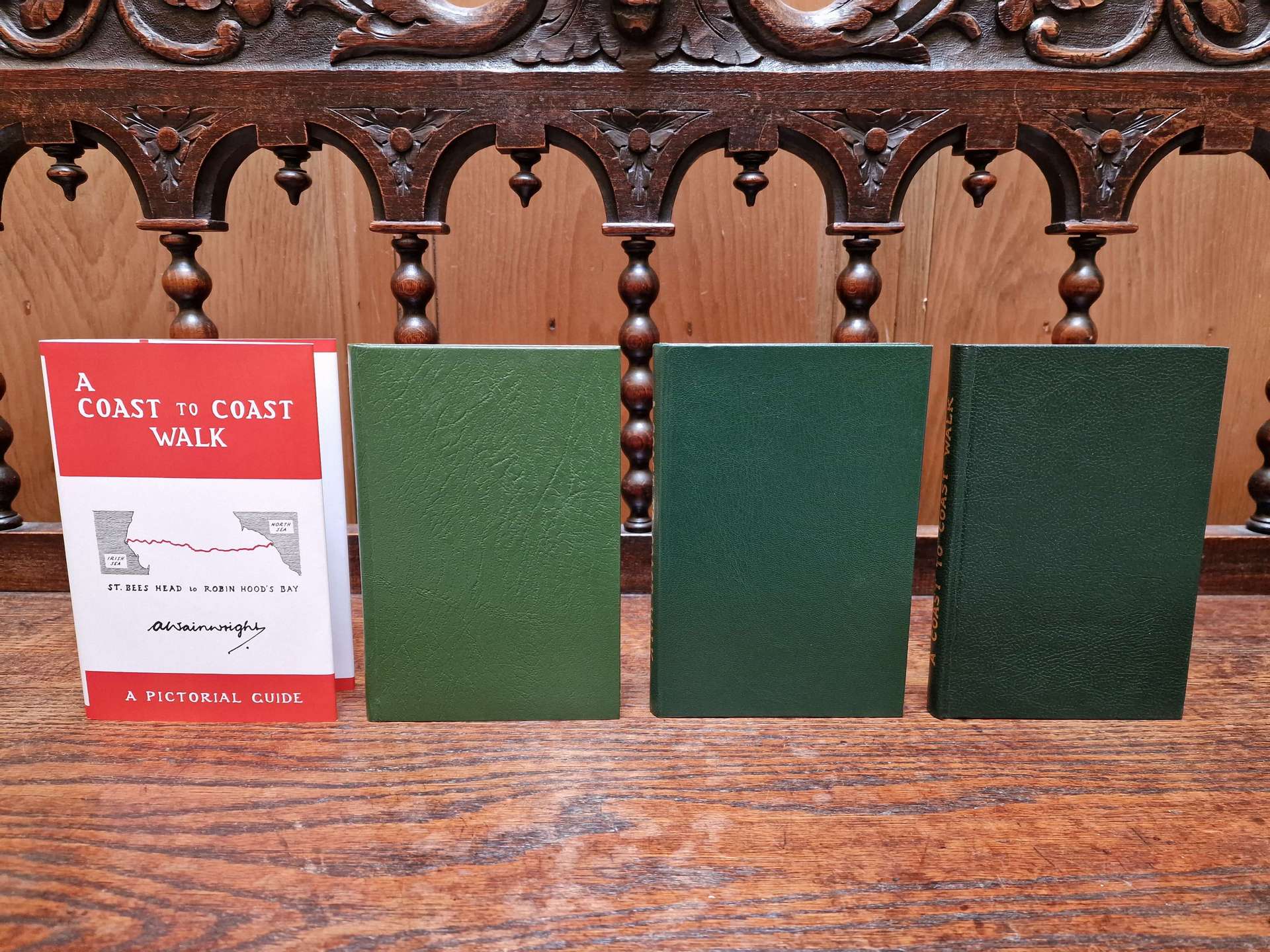

The eighteenth and nineteenth impressions marked the conclusion of the blue guides from 1979, distinguished by gold blocking on the front. Starting in 1980, all Pictorial Guides uniformly adopted a plain green case, maintaining this consistent appearance for nearly a decade.

The use of impression numbers ceased by late 1985, with the final guides bearing them retailing at £4.65. Subsequently, the price increased to £5.50, coinciding with the disappearance of all impression numbers. A Coast to Coast Walk achieved the thirty-fourth impression, surpassing the sales of The Outlying Fells of Lakeland, originally published in 1974.

A dedicated Coast to Coast Walk BBC TV series featuring Wainwright aired in September 1989. Before the series aired, the Westmorland Gazette printed an additional 10,000 copies of the A Coast to Coast Walk guidebook. Still, it wasn’t enough, making it the biggest-selling Pictorial Guide of that year.

Following the broadcast of the new TV series, Wainwright revisited St Bees in the late summer of 1989 to commence the creation of a sequel to his acclaimed A Coast to Coast Walk. Additional details can be found in Wainwright Memories.

Wainwright’s A Coast to Coast Walk underwent several revisions from 1973 to 1990, with many adjustments prompted by the trail traversing private lands. A notable alteration occurred beyond Beacon Hill, near Orton. Ongoing abuse by walkers, including camping, wall damage, and littering, led farmers to revoke access permission. Despite Wainwright’s warning to readers in 1976, the situation persisted. In 1981, the route was redirected through Orton, adding two miles to the walk as a response to the farmers’ decision to withdraw access.

Here is a list of the changes made by Wainwright during the Gazette years, apart from one by Chris Jesty.

Page 7:

In 1974, Wainwright diverted the walker away from a private lane.

Page 47:

In 1974, Wainwright edited two incorrect village names on the map. Howtown was changed to Hartsop.

Page 75:

In 1974, Wainwright warned walkers away from a path on private land.

Page 117:

In 1975, Wainwright reported that refreshments could now be found at Danby Wiske.

Page 63:

In 1976, Wainwright reported that the route from Beacon Hill onwards was private ground and respected the farmers’ land after receiving complaints of damage to walls.

Page 58:

In 1981, Wainwright extended the Shap to Kirkby Stephen section from 20 miles to 22.

Pages 62/3:

In 1981, Wainwright received more complaints from farmers about walkers camping, damaging walls, etc. Permission to follow the path beyond Beacon Hill has now been withdrawn. Wainwright made significant changes to the route, which now diverts through Orton.

Page 65:

In 1981, Wainwright made more changes as the new route through Orton added two miles.

Page 115:

In 1981, Wainwright added Orchard Farm to the map.

Page 125:

In 1985, Wainwright made his final amendment, adding a Youth Hostel near Osmotherley.

The surge in popularity led to a significant revision to the route in January 1990. Andrew Nichol, the General Printing and Book Publishing Manager at the Westmorland Gazette, received a strongly worded letter from the British Rail Property Board. The complaint focused on the Coast to Coast Walk crossing a level crossing at Stanley Pond, where no right of way existed. The complaint, accompanied by detailed documentation, included a threat of legal action if the route was not altered. Andrew found the situation excessive and reflected that a straightforward phone call to discuss the issue could have sufficed.

Andrew personally inspected the route to verify the safety concerns at the level crossing. Subsequently, he communicated the details to Wainwright and outlined the necessary changes for the guidebook. However, a hurdle emerged as Wainwright’s eyesight posed a challenge. Recognising the similarity between Wainwright’s handwriting and that of local author and cartographer Chris Jesty, Andrew proposed Chris as a suitable collaborator. Wainwright agreed, providing Andrew with the accurate wording, which Andrew then conveyed to Chris in written correspondence.

The following passages were taken directly from Chris’s 1990 diary:

Saturday, 10 February – ‘I received a letter from the Westmorland Gazette asking me to do a small amount of revision to the Coast to Coast Walk. Every time I get one job finished, another one comes along. I worked out a new text that would be roughly the same length as the old text and just managed to get it off in time for the 12.15 post.’

‘Revising the Wainwright books was what I set out to do in 1980, so now both my ambitions have been fulfilled, though on a smaller scale than I had envisaged.’

Tuesday, 13 February – ‘Finished revising two pages of the Coast to Coast Walk and sent them to the Westmorland Gazette. They took 11½ hours.’

<<>>

The revised route takes a slight southern detour to circumvent the level crossing. Chris’s subtle changes and handwriting’s seamless integration harmoniously complement Wainwright’s style. Until the next reprint, a two-page erratum outlining the adjustments was produced and inserted into all existing copies of the book in stock.

A few months following Wainwright’s passing in January 1991, the publishing rights transitioned to Michael Joseph. Under the new publisher, the guidebooks were scheduled for a relaunch in April 1992. Chris Jesty personally penned the new prelims, and Michael Joseph collaborated with Titus Wilson to craft fresh designs for the dust jackets.

The spring 1992 launch proved highly successful but wasn’t without challenges. Michael Joseph, the new publisher, found themselves grappling with many inherited issues. Within six months, a slew of complaints regarding the Coast to Coast Walk would arrive at the doorstep of the new publishers:

Independent

Saturday 17 October 1992

By Peter Dunn

ALFRED WAINWRIGHT, a curmudgeonly loner whose walking guides to the brooding fells of northern England made him world-famous, became an unwitting accomplice to an offence that must have appalled him – the despoliation of the countryside he loved.

This is the great paradox of the stonemason’s son and town hall ledger clerk who died last year, aged 84: his 12 handwritten Pictorial Guides, full of irascible humour that endeared him to generations of hikers, have sold one and a half million copies since he published the first one in 1955. Like Peter Mayle’s books on Provence, they consign an endearing and irresistible dream of simple country life to the supermarkets of mass tourism.

The damage is widespread and proliferating fast. Seven of the most popular Wainwrights cover the Lakeland fells, where he worked as borough treasurer in Kendal town hall for many years; two others, covering the Pennine Way and coast-to-coast walk (which Wainwright invented) have become bibles to generations of followers stumbling through hell and high water in their guru’s grumbling footsteps, often far from a right of way.

As a younger man, it never occurred to him that he was lighting a slow fuse under a time bomb. He wrote the books for his own pleasure, as memoranda, to browse through when he retired to his house, which had breathtaking panoramic views near Kendal. ‘I wrote . . . not for material gain,’ he said in his first one, a guide to the eastern fells, ‘not for the benefit of my contemporaries, though if it brings them also to the hills, I shall be well pleased. Certainly not for posterity, about which I can work up no enthusiasm at all.’

The guides were written in his ledger clerk’s hand because he never trusted the printers to get it right, even at the little Westmorland Gazette publishing house. Written with infinite care – a single page could take a day to complete – they conveyed a sense of almost medieval simplicity, a purple homage to ‘the lonely ridge, the dancing beck, the silent forest’.

In reality, the pressure of legions of heavy boots trampling wildlife, gouging highways through soft peat moorland, and vandalising ancient monuments has inflicted a different kind of legacy across some of the wildest areas of rural England. Landowners, across whose acres Wainwright’s routes sometimes trespass, are beginning to count the cost and ask who should pay for it.

A year ago, Wainwright’s copyright was acquired by London publisher Michael Joseph, and its nationwide promotion of the guru’s works increased commercial and physical pressures as the guidebook trade competed for the attention of thousands of ramblers.

Publishers and conservationists are focusing their attention on the guru’s most popular walk, the coast-to-coast, a 190-mile slog from St Bees in Cumbria across the lakes, dales, and moors to Robin Hood’s Bay on the Yorkshire coast. Here, across Wainwright’s ‘eternal hills,’ a publishing war is coming briskly to the boil (see below), and questions are being raised about the sanctity of the guru’s works of art.

A year after acquiring and relaunching Wainwright’s 12 Pictorial Guides from the Westmorland Gazette, the London company has encountered severe problems with north country conservationists and landowners.

Unlike the Pennine Way, the coast-to-coast is not a designated trail; unknown to most walkers, 40 per cent of its western route involves trespassing across private land, including Lord Peel’s estate in the Yorkshire Dales. It is to Wainwright’s path through this area, roughly a 22-mile stretch from Shap to Nine Standards Rigg, near Kirkby Stephen, that Michael Joseph is being asked to make significant changes to the drawings and handwritten text of Wainwright’s book. The intention is to divert walkers away from sensitive wildlife areas and important archaeological monuments.

The company has rejected pleas that Wainwright’s hallowed book is now so outdated that it should be scrapped as a guide. The alternative, now under negotiation, is to fill it with scraps of addenda – typeset warnings about trouble spots and diverted paths. It refuses to make any other significant changes on the grounds that Wainwright’s original is a work of art. Conservationists fear that many walkers, disciples of Wainwright, will insist on following in the guru’s sacred footsteps.

Michael Joseph is also resisting pressure to use some of the profits from its Wainwright imprint to help pay for the restoration of damaged terrain and way-marking diversions across private land, which, unlike public rights of way, the county council highways departments do not have to maintain.

The question of liability for guides which, technically at least, encourage ramblers to trespass (one new guide in the northern Pennines has eight of its 14 walks crossing private land) has set alarm bells ringing throughout the highly competitive guidebook market.

Anthony Kilvington, a solicitor in Kirkby Stephen who has shooting rights on moorland damaged by coast-to-coast walkers approaching Nine Standards Rigg, puts it this way: ‘No landowning family would say they didn’t want the path today because that would be selfish, but the moor isn’t meant for that number of people, and I’ll be writing to Michael Joseph about it in general. I feel that once it’s been pointed out to them that part of the route is not a public right of way, they’re certainly putting themselves at risk from litigation. The moral issue certainly is that if there’s damage, they should put it right.’

Michael Joseph’s miseries are being followed with scant sympathy by rival publishers in the North. ‘I think personally they don’t see the problems because they’re a London publisher and not au fait with what goes on in the countryside,’ says Walt Unsworth, director of Cicerone, publishers of activity guides in Milnthorpe, Cumbria. ‘When they got the Wainwright books, they thought they were buying golden apples; instead, they’ve found in the tree a hornet’s’ nest.’

More than any other long-distance walk in Britain, the coast-to-coast has become a victim of its own success. Promoting the route in a series of television programmes in 1985 starring Wainwright has made it Britain’s most popular obstacle course. Wainwright himself recognised its unique qualities. ‘The Pennine Way is masculine,’ he said. ‘If there happens to be something in your temperament that makes you like the ladies, the odds are that you will prefer the coast-to-coast.’

In two years, it has become big business for publishers and village traders across the North of England’s most marketable route. Even the physical pain has been removed. A pack shuttle service operated from Kirkby Stephen offers to carry rucksacks between overnight stops at pounds 3 a time. According to one estimate, the coast-to-coast, a creation of Wainwright’s solitary imagination, is now tramped by 20,000 hikers yearly.

This kind of pressure —and its consequences alerted Andrew Nicholson of the East Cumbria Countryside Project. The Countryside Commission backs the project and specialises in shuttle diplomacy between landowners and the access lobby. In a series of letters, Mr Nicholson asks Michael Joseph to alter key sections of its coast-to-coast guide before a reprint is issued next year.

These include travelling east from Shap, Black Dub, a monument to Charles II on Crosby Ravensworth Fell that tempts walkers off the route onto a Site of Special Scientific Interest – a breeding ground for moorland birds, including the golden plover (his request for the Black Dub drawings to be removed has been rejected); Sunbiggin Tarn, a grade one SSSI, botanically very sensitive and now showing signs of damage and litter; Rayseat Pike long barrow, a neolithic cairn described by county archaeologists as a site of national importance and now vandalised by walkers who have erected a stone-built wind shelter; and the Severals Village Settlement, a complex of prehistoric villages. Paul Cairns, a chip shop owner in Kirkby Stephen who owns land around Sunbiggin Tarn and used to breed ducks there, is particularly alarmed about increased pressure over his wild acres.

‘I’ve written to my MP, Michael Jopling, about it and David MacLean, the environment minister,’ he says. ‘When it comes to spring, you’ve got all those nesting birds, and for all we use it for shooting, it’s crucial nesting birds get a bit of peace and quiet, and they’re not getting it. They’re all so colourfully dressed, these walkers; it frightens birds from miles away anyhow. The way they go about it, they seem to head for the most difficult place to cross. And we’re getting tins and bottles up there, which we didn’t used to have. These publishers print all these books. They’re the only ones that’s making money out of it.’

Mr Nicholson says Michael Joseph’s reaction to his letters has been less cooperative. ‘They’ve said they’ll take on board variations to the route by inserting typeset amendments, and that’s good,’ he says. ‘The bad news is they don’t want to make any changes to the book itself on the grounds that it’s a work of art. This brought a pretty hefty response from a whole range of individuals, including ourselves, the Country Landowners Association and the National Farmers’ Union. Michael Joseph told me they’ve had a lot of flak about it. What worries me a lot is the purists who think his book is the Bible.

‘We’ve suggested that one way out would be to print the original Wainwrights as hardbacks with fancy bindings, ideal for collectors. A cheaper walking manual incorporating the changes could be produced that people could use with confidence. Michael Joseph said that would be too expensive and won’t do it.

‘The argument about whether it’s commercially viable to produce two editions isn’t really a strong one if you’re faced with people in the countryside suffering real problems. I’ve also written to Michael Joseph twice requesting that they donate something towards repairs, but the response hasn’t been promising. They’ve stated that they can’t consider any funding.

‘There’s a responsibility issue involved. Walkers are causing damage. In that light, it’s difficult to imagine any consideration other than the fact that the author and publisher have a duty here. Repairs around Nine Standards will run into thousands rather than hundreds.’

Jenny Dereham, the editorial director of Michael Joseph, takes a firm line about preserving the original books. ‘That’s what Wainwright wanted, and that’s what the estate wants,’ she says. ‘All I know is that when it was intimated we were going to make changes, we had a huge postbag saying it was outrageous.

‘On the other hand, we see that we are obligated to private landowners and conservationists. If we can retain the original but add an addenda saying, ‘We think this is a better route,’ then we’ll do that. We’re still making decisions about it.

‘We simply can’t at the moment consider accepting Mr Nicholson’s request to double-publish. We’re in a recession, end of comment. We’ve put an enormous amount of money into these books. I’m talking about our promotion in April to get them sold throughout the country.

‘For the same reasons, we can’t consider contributions to maintaining or repairing the coast-to-coast path. Maybe one day, when we’re actually showing a profit on these books, but not now.

‘If the time comes when we’ve more typesetting than handwriting in the Coast to Coast, we’ll have to think again about what we can do.’

Mr Kilvington cannot understand the publisher’s obduracy. ‘It’s all very well for Michael Joseph to call it a work of art,’ he says. ‘The fact is that Wainwright if shown to be wrong, was very quick to redress the situation, and I know this from personal experience.

‘From what you read about the man, he was basically a loner. Some of the places he discussed were very personal to him. I can’t believe he would have wished so many people to share it, to spoil the very thing he thought so much of.

‘If Michael Joseph won’t help, then what happens next will depend very much on the attitude of landowners. It will depend on whether any landowner wishes to take Michael Joseph on and, presumably, that would be a big landowner, someone as big as Michael Joseph. When they say work of art, they’re talking about possible loss of profits, aren’t they? They should be as big as Wainwright about it. The book’s just one man’s wanderings, really. It’s not an oil painting, for God’s sake.

<<>>

The initial launch books were reasonably priced at £8.99. However, a few months later, the printing of the guidebooks shifted to Clays Ltd in Suffolk. This development proved disheartening for Titus Wilson and dealt a significant blow to Kendal. A firm decision was made to ensure that no original printing materials left Kendal. Titus Wilson maintained possession of the original negatives for the Wainwright books, with Michael Joseph being provided with a duplicate set.

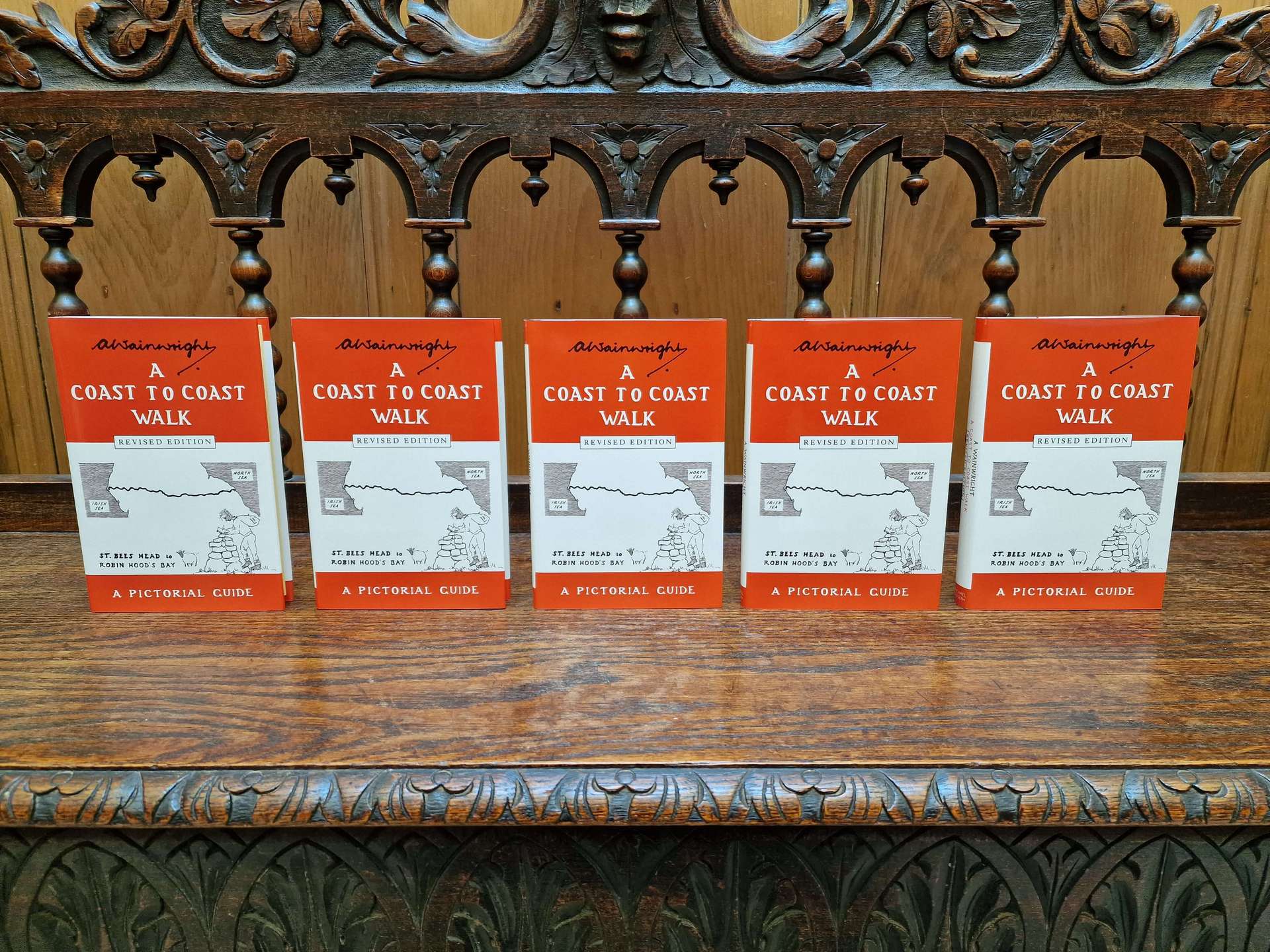

The new publisher faced pressure to revise the guides, particularly A Coast to Coast Walk, but steadfastly refused, leaving Chris Jesty disheartened. Nonetheless, specific route changes became unavoidable. Chris was granted authorisation to implement these minor alterations, leading to the publication of a new Revised Edition in 1994. Subsequent minor adjustments were made in 1995 and 1998. Michael Joseph produced five revised impressions of the guidebook, available at retail prices ranging between £9.99 and £12.99.

From left to right:

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE), M. Joseph 1994

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) revised, M. Joseph 1995

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) revised, M. Joseph 1998

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE), M. Joseph 1999

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE), M. Joseph 2001

Chris remained dissatisfied with the minor revisions and desired to overhaul the entire book. The additional work, being typeset, failed to integrate with Wainwright’s authentic, organic handwriting.

Sales experienced a rapid decline in 2001, with the foot and mouth outbreak being the suspected cause. In response to the challenging market conditions, Michael Joseph halted the publication of the guidebooks in January 2003. This marked the first time Wainwright’s work had been out of print since 1955. Within a month, Frances Lincoln successfully bid to republish them. After a decade-long absence, Wainwright’s works of art would again find their rightful home in Kendal.

Unfortunately, the original negatives were missing when Titus Wilson sought to reprint the A Coast to Coast Walk – Revised Edition. In lieu of this, an existing book was meticulously disassembled and scanned at a high resolution. Positives were then generated from these scans to facilitate the reprinting process.

In 2019, David Rigg, the owner of Titus Wilson, kindly appointed me as the custodian of all existing Wainwright printing materials. The process of locating everything, undertaken with my wife, spanned several weeks. Remarkably, we stumbled upon the missing original printing negatives for A Coast to Coast Walk during the search. These negatives, absent since their last use in 1992, were found in a location one wouldn’t even consider looking.

The guides were officially launched in April 2003, priced at £11.99. To meet the increasing demand, Titus Wilson expanded its team and constructed a new warehouse for stock storage. Over the next two years, Titus Wilson experienced a busy period, notably with the introduction of the new 50th Anniversary Editions. However, in 2006, rising printing costs prompted the removal of the books from Titus Wilson. Despite their efforts to retain the publications in Kendal, Frances Lincoln, a business prioritising profits, ultimately decided otherwise.

The 50th Anniversary Editions, printed in Kendal, featured a special ‘cream wove’ paper meticulously chosen to replicate the texture of the original First Edition guides. This distinct paper was locally sourced from James Cropper in Burneside. The surplus sheets were then repurposed for the second impression of A Coast to Coast Walk – Revised Edition.

From 2006 to 2010, nine additional impressions were printed in multiple locations, including Singapore, Thailand, and China. Each impression bears unique physical distinctions and was initially priced at £12.99, later increasing to £13.99.

From left to right:

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) Singapore, F. Lincoln 2003

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) Thailand, F.Lincoln 2003

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) Thailand, F. Lincoln 2003

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) Thailand, F. Lincoln 2003

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) Thailand, F. Lincoln 2003

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) China, F. Lincoln 2003

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) China, F. Lincoln 2003

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) China, F. Lincoln 2003

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) China, F. Lincoln 2003

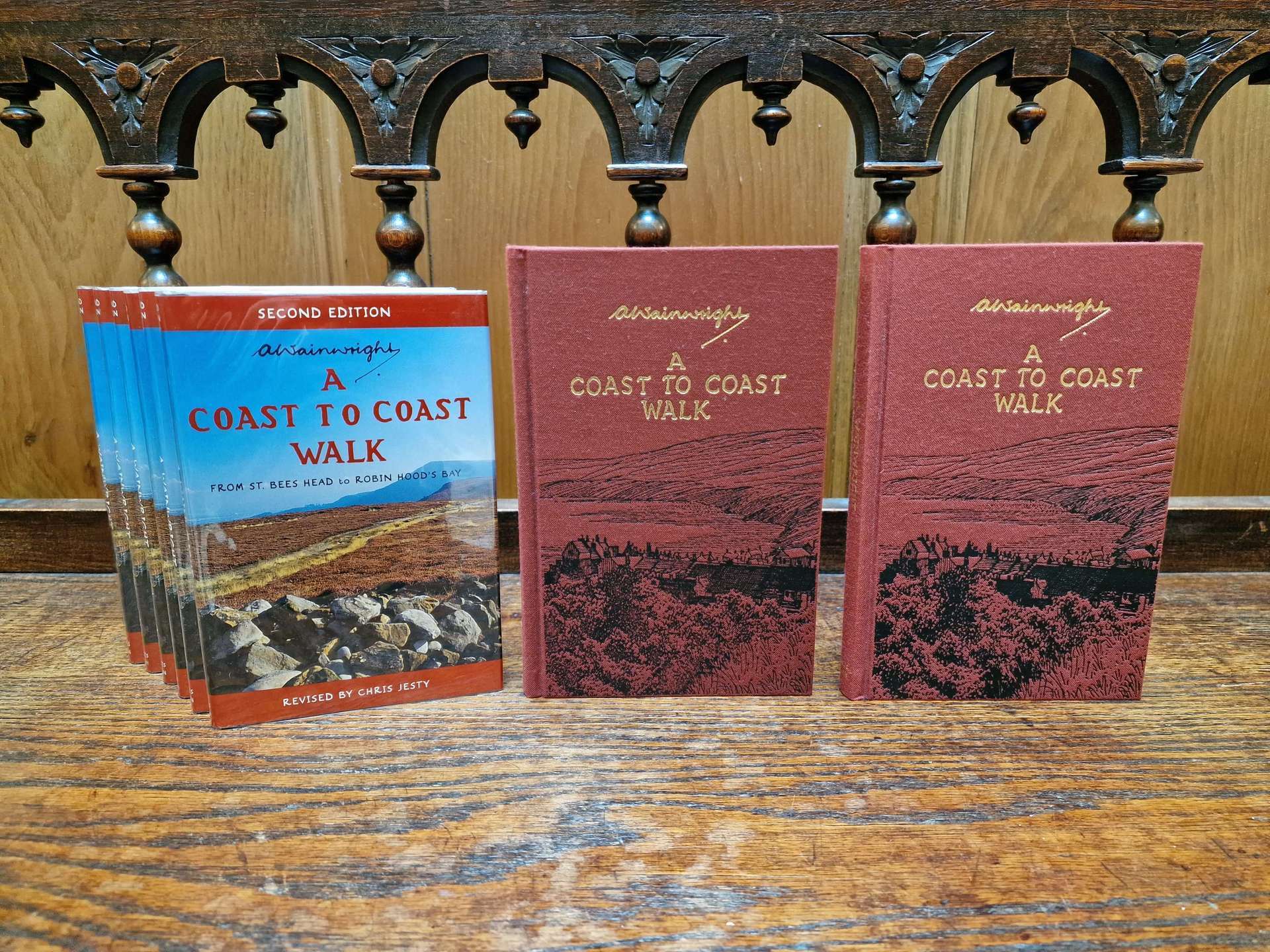

In contrast to Michael Joseph, Frances Lincoln embraced comprehensive revisions. In 2005, Chris Jesty finally realised his long-held desire to revise all twelve guidebooks, dedicating a decade of his life to the endeavour. A Coast to Coast Walk – Second Edition, replacing the old Revised Edition, was published in 2010. Six impressions were printed and retailed between £13.99 and £14.99. With this update, Wainwright’s original narrative was officially out of print.

From left to right:

A Coast to Coast Walk (SE), F. Lincoln 2010

A Coast to Coast Walk (SE), F. Lincoln 2010

A Coast to Coast Walk (SE) revised, F. Lincoln 2011

A Coast to Coast Walk (SE), F. Lincoln 2011

A Coast to Coast Walk (SE) revised, F. Lincoln 2014

A Coast to Coast Walk (SE), F. Lincoln 2014

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) low gsm paper, F. Lincoln 2009

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) high gsm paper, F. Lincoln 2009

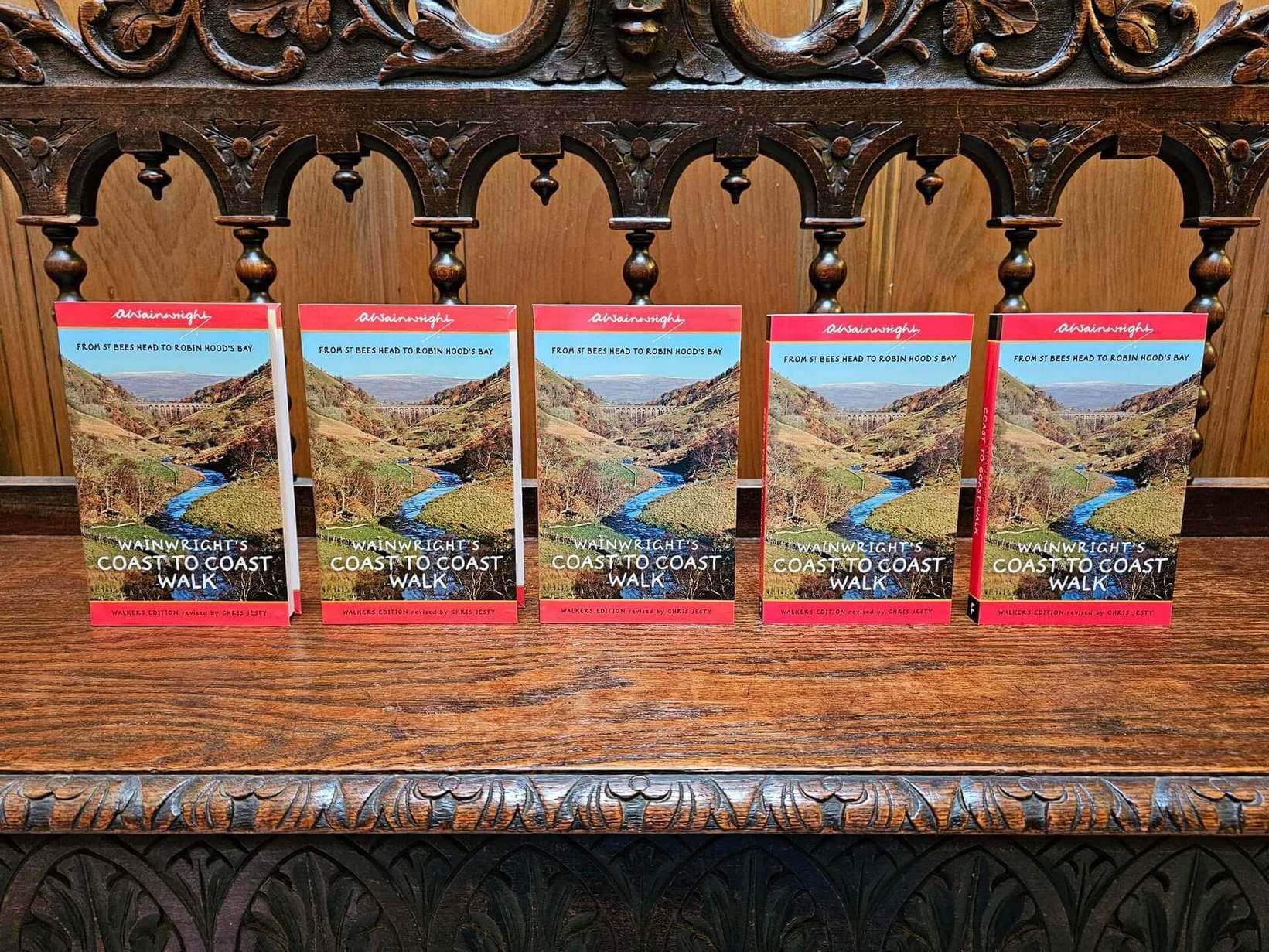

In 2017, the guide was renamed Wainwright’s Coast to Coast Walk – Walkers Edition. The format was changed to flexibound, incorporating minor route adjustments. Three flexibound impressions were produced until they were eventually succeeded by paperbacks in 2022.

From left to right:

Wainwright’s Coast to Coast Walk (WE) flexibound, F. Lincoln 2017

Wainwright’s Coast to Coast Walk (WE) flexibound, F. Lincoln 2017

Wainwright’s Coast to Coast Walk (WE) flexibound, F. Lincoln 2017

Wainwright’s Coast to Coast Walk (WE) paperback, F. Lincoln 2022

Wainwright’s Coast to Coast Walk (WE) paperback, F. Lincoln 2022

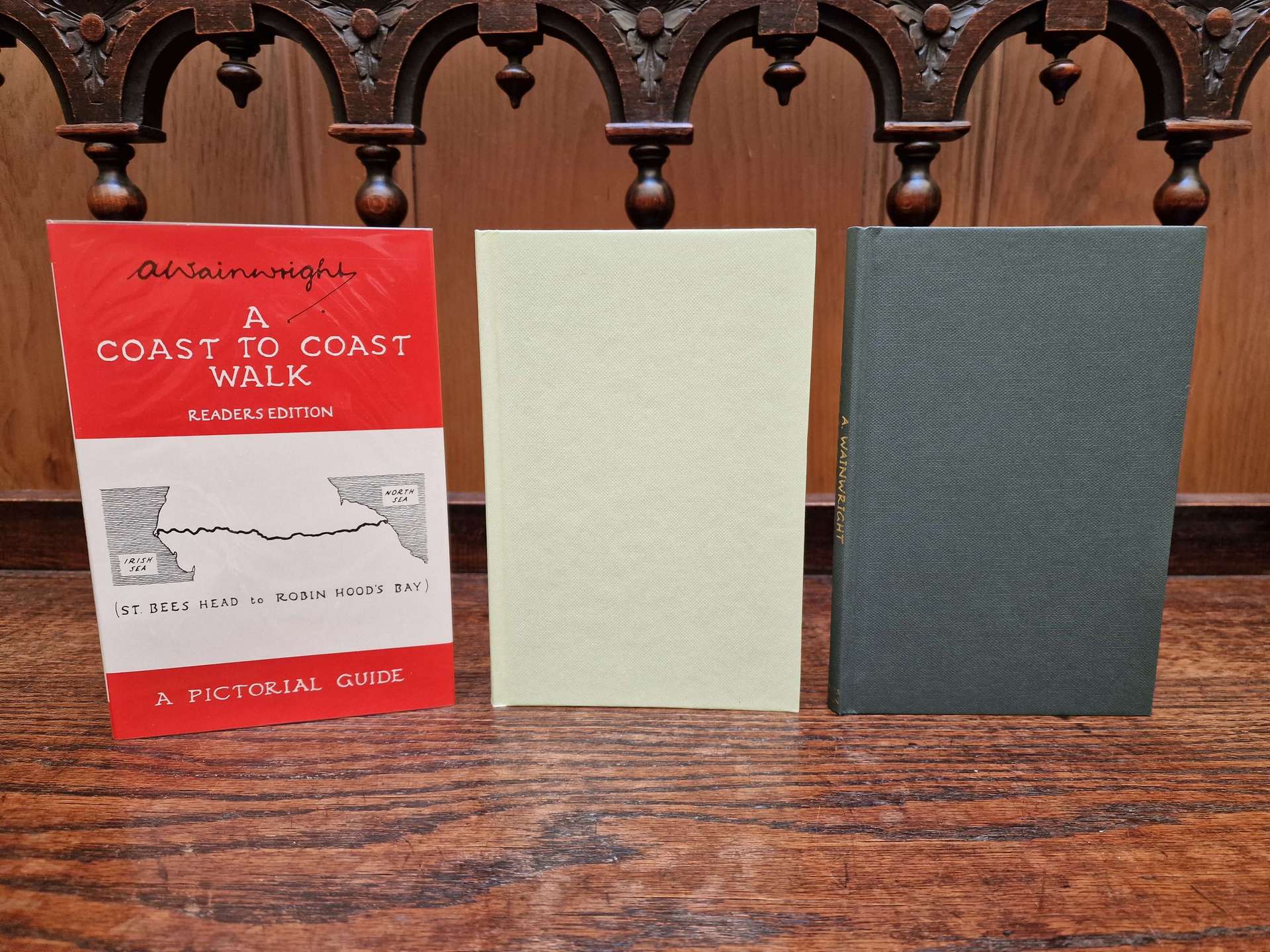

Wainwright’s original A Coast to Coast Walk was reprinted (hardback) in 2017 and rebranded as the Readers Edition. The guide came with a cautionary note advising that the route information might be outdated and that readers undertaking the trail should consult the new Walkers Edition.

In 2022, after just two hardback print runs, A Coast to Coast – Readers Edition was reprinted as a paperback.

From left to right:

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) hardback, F. Lincoln 2017

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) hardback, F. Lincoln 2017

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) paperback, F. Lincoln 2022

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) paperback, F. Lincoln 2022

A Coast to Coast Walk (RE) paperback, F. Lincoln 2022

<<>>

My wife and I undertook the Pennine Way in 2013 and the Coast to Coast Walk in 2015. Our experiences on both trails were thoroughly enjoyable, although I can’t entirely align with Wainwright’s critiques of the Pennine Way. Contrary to his opinions, we found immense satisfaction in the extended, seemingly featureless moorland sections—they offered a unique sense of isolation from civilisation, which proved refreshing. After completing the walk, readjusting to the realities of the outside world took some time.

Our experience on the Coast to Coast Walk was markedly different. The walk was excellent, and the scenery surpassed that of the Pennine Way. However, the distinctive sense of solitude on Pennine Way wasn’t as pronounced as on Coast to Coast Walk. Perhaps the walk has become a victim of its own success, a popularity that Wainwright likely didn’t anticipate. Upon learning of an American group walking it, he quipped to a friend, “Haven’t they got their own walk?” which elicited a chuckle.

In summary, the Coast to Coast Walk is a must for anyone who enjoys long-distance hiking. Wainwright’s vision was indeed ingenious, and the walk is a testament to his brilliance. Over time, it has become one of the most popular and iconic walks globally.

“One should always have a definitive objective, in a walk as in life—it is so much more satisfying to reach a target by personal effort than to wander aimlessly. An objective is an ambition, and life without ambition is…..well, aimless wandering.” A. Wainwright.

Back to top of page